Gustav Mahler: The Arduous Road to Vienna (1860 – 1897) by Henry-Louis de La Grange, completed, revised and edited by Sybille Werner. Pub. Brepols N.V., 809 pp. ISBN: 978-2-503-58814-8

By Stephen Cera

Henry-Louis de La Grange was smitten with Mahler’s music in 1945, at age 21, on hearing Bruno Walter conduct the composer’s Ninth Symphony at Carnegie Hall. The impact of that performance (which predated the “Mahler boom” of the 1960s) sparked an obsession that led the French scholar to devote his long life to championing and chronicling the composer. The fruit of his singular devotion was a massive four-volume biography, the first volume of which appeared in 1973.

Since then, worldwide interest in Mahler has grown immensely, along with a flood of research. This prompted La Grange to undertake an update of Volume One, but he died before it could be completed. The task of integrating all the new material fell to Sybille Werner, who had worked with the French scholar on this update from 2011 until his death in 2017. Werner, a noted authority on the performance history of Mahler’s works and a conductor of high achievement, completed the project with distinction. The new volume not only reads smoothly, it overflows with absorbing detail about Mahler’s thoughts on music and philosophy; his reading; profound attachment to nature; important relationships with women; and all-embracing vision both as a creator and re-creator.

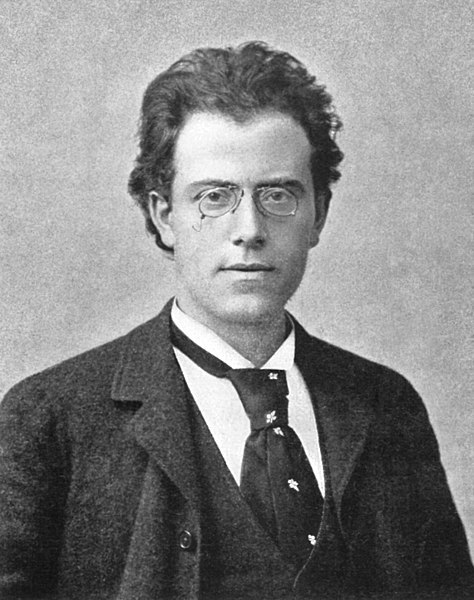

Gustav Mahler in Hamburg in 1892

Among the material that surfaced since 1973 are studies of Mahler’s friends and his early intellectual and musical development; specialist exploration of his formative years in Bohemia and Moravia, and of Jewish life in those regions before he was born; and collections of correspondence. Other recent sources addressed his years in Budapest, Leipzig, Hamburg and elsewhere. Newspaper and magazine articles were unearthed and translated.

Prior to 1973 there had been other, less ambitious Mahler biographies – plus reminiscences, memoirs, books of letters — but none before La Grange had mined every possible shred of source material, setting it all squarely in the context of the musical world that Mahler inhabited and shaped.

The French biographer focused more on Mahler’s life than his works. Thanks to this orientation, a comprehensive portrait of Mahler’s complex personality finally emerged. Before La Grange, we were more familiar with Mahler’s music than with his life.

Yet writing music was not Mahler’s primary occupation. Rather, he was one of the leading opera and symphony conductors of his time, juggling a hectic schedule of auditions, rehearsals, performances, and touring during non-summer months, as well as stage directing and administrative work. This activity, documented here in detail, fertilized his ongoing work as a composer. The surprise is that he never composed an opera.

Mahler’s place in the pantheon today is because of his composing, not his career as a major conductor. The authors offer valuable insight into the creative processes of Mahler the path-breaking composer and orchestrator of gigantic symphonies whose innovative musical language – subjective in expression and constructed with rigorous intellectual control — straddled the 19th and 20th Centuries. These works expanded the meaning of “symphony” as they stretched the size, scope, forces, and affective range of the orchestra.

The first three symphonies, Das Klagende Lied, the Songs of a Wayfarer and many other songs date from these early years, during which Mahler was crossing paths with such iconic figures as Brahms (who became his friend and supporter after hearing him conduct Don Giovanni in Budapest), Bruckner, Tchaikovsky, Busoni, and Richard Strauss; Wagner’s widow, Cosima, and others. Still earlier, there was a fleeting encounter with Richard Wagner himself. As a 15-year-old student, Mahler froze in awe as he observed the elder composer struggle to get his arms into an overcoat following a winter concert in Vienna. (Incidentally, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus opened in August 1876; the new volume pegs the year as 1872.)

Mahler the conductor steadily worked his way up the professional ladder after years in provincial theaters. Eventually, he assumed artistic command of such major European opera houses as those of Prague and Leipzig, before moving up to Budapest and Hamburg.

His ultimate goal was never in doubt, and Mahler’s crowning appointment came as Director of the Vienna Court Opera (now the Staatsoper) at age 37. This is where the new volume ends. (After turbulent years in Vienna, Mahler went to New York and conducted at the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic, before returning to Vienna where he died of a heart ailment at age 50.)

La Grange and Werner devote generous space to press reviews of Mahler-led performances, many of which subjected the conductor to critical slings and arrows. Reviews of the premieres of his compositions were sometimes vitriolic; few prefigured Mahler’s current position in the firmament of great composers.

Conflicting as those press accounts may have been, they provide a backdrop of the cultural climate in which the composer functioned. Probably none describes Mahler’s actual music-making quite as succinctly as did the late Otto Klemperer: “When he [Mahler] conducted you felt it couldn’t be better and it couldn’t be otherwise.”

Alas, there are no recordings of Mahler on the podium, though he did make some Welte-Mignon piano rolls of his own music in 1905. (Commercial recordings of his works began to be produced a few years after his death in 1911.)

In documenting Mahler’s life, La Grange and Werner cite written correspondence of a kind that is no longer part of our lives in this era of e-mails and texting. They offer revelations about Mahler’s repertoire (e.g., in his mid-thirties, he conducted no fewer than 54 different operas in one season, including some surprises, such as his championing of Wagner’s Rienzi, Cornelius’s Barber of Baghdad, Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel, and works by Mascagni.)

The new volume is more handsomely produced than the original Volume One, boasting a larger format with heavier paper stock, and more navigable appendices. Its thoroughness and mountain of detail are staggering. We should reflect that creating this mammoth Mahler biography took almost as much time as Mahler’s whole life.